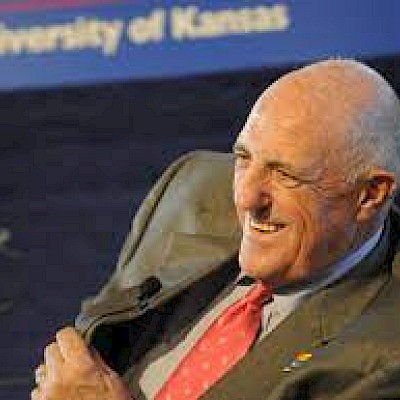

Roger Thibault

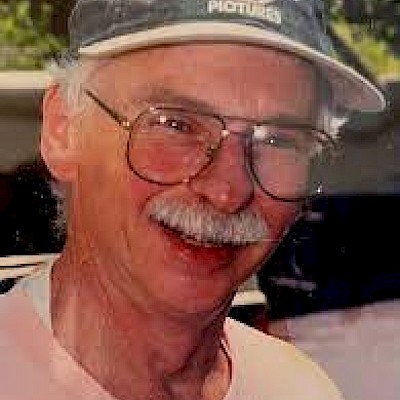

Roger Thibault, who was legally joined with Theo Wouters in Quebec’s first same-sex civil union, has died.

He passed away at their home in Pointe-Claire in Wouters’s arms. They had been together for 50 years.

Thibault was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease six years ago. Wouters cared for him at their home until the end. He died from complications from the disease. He was 77 years old.

“He was the kindest man, and he loved me to bits,” Wouters said. “Even in his last moments, he really loved me, and I loved him.

“I have so much to treasure in my memories with him.”

On July 18, 2002, Wouters and Thibault became the first same-sex couple to be legally joined by civil union in Quebec, two years before the province would legalize same-sex marriage.

In an interview with the Montreal Gazette on the 20th anniversary of their union, the couple said they had no idea what a momentous occasion it would turn out to be until they arrived at the Montreal courthouse, greeted by a throng of photographers and reporters. Strangers rushed across the street to bring them a bottle of wine. Lawyers and clerks lined the upper levels of the courthouse to get a glimpse of the historic moment.

After years of advocacy, the civil union had been established by the Quebec government a month earlier. Since same-sex couples still couldn’t legally wed, it worked as an option that would give them many of the same legal benefits as married couples.

The civil union would soon be overtaken in popularity by same-sex marriage, but it was hailed at the time as a progressive step forward for the province.

“(Quebec) became one of the first places in the world to put forward that two people of the same sex could legally unite together, sharing the same rights and obligations,” said Patrick Desmarais, president of Montreal’s Fondation Émergence, which specializes in fighting homophobia and transphobia, on the 20th anniversary of the union. “And it brought on this push for equality between all people.

“I think it did a lot to educate and sensitize the general public in Quebec and Canada,” Desmarais added. “It really opened the public’s eyes to the fact that it could be possible, and could be legal, and that two people of the same sex uniting didn’t change anything in anyone else’s lives.”

For Wouters and Thibault, the union was largely symbolic after nearly three decades together, beginning when the two met at a gay bar on Mackay St. in Montreal. But they felt it had to be done as part of the greater good, and to send a message.

“At first we said we don’t really need to get married,” Wouters said. “We were already committed in life. But then we thought it over because we were so well known.”

Once it was done, Wouters said, they were also happy to be protected by the same laws that applied to other couples, “because we had been hearing so many horror stories when families get involved when one partner dies.”

Ironically, the couple’s historic union was born partly of hatred. They had been the subject of homophobic slurs, insults, and threats for over a decade, which ultimately spurred a march outside their Pointe-Claire home that drew thousands who showed their support of the couple. That would lead to the creation of the International Day Against Homophobia, and their civil union.

“We were sort of forced to do so because of the situation here,” Wouters said. “It lasted for 10 years, this horrible, horrible hatred — I still cannot believe that people can hate for absolutely nothing.”

While the union brought them fame and accolades, Wouters noted that the hatred continued, and still does to this day. The current political climate, particularly in the United States, means that “we have to be very vigilant that this doesn’t slip into Canada,” he said.

When they first met, Wouters, who is of Dutch heritage, didn’t speak a word of French, and Thibault couldn’t speak any English. So they communicated by sign language, and a relationship that would last half a century was born. Wouters was a fashion designer, creating clothes and hats for Canada’s rich and famous. Thibault was a photographer, working in the department of industrial design and architecture at the Université de Montréal.

“We were quite committed from Day One,” Wouters said. “We were very much aware that we were blessed because, in the gay community, it is not a usual thing for people to stay together for so long.”

The union stayed strong in part because they shared many projects together, including collecting more than 140 tons of rock “from everywhere” to create their elaborate garden in Pointe-Claire.

“When you do projects together in everything, as part of your daily activities, then you have a much better chance to really stay a lifetime together,” Wouters said.

Another project became battling homophobia, which would cost them countless hours, over $240,000 in legal fees, and the loathing of people they had never met.

“It was difficult sometimes to scrape the funds together to pay the lawyers, but we managed,” Wouters said.

In May of this year, Thibault and Wouters were made honorary citizens of Montreal in recognition of their decades-long fight to advance LGBTQ2+ rights.

“We’re very happy that it inspired so many people. We never thought that that would be the case,” Wouters said. “But it was the case.”

•

Remembering Roger Thibault

Use the form below to make your memorial contribution. PRO will send a handwritten card to the family with your tribute or message included. The information you provide enables us to apply your remembrance gift exactly as you wish.