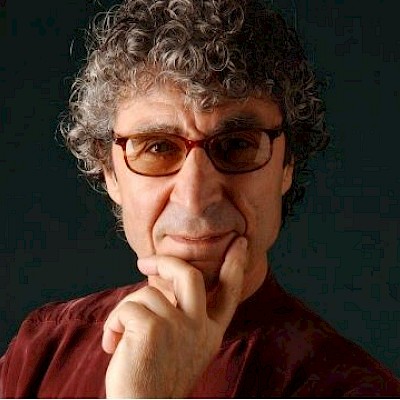

Jean Shepard

Jean Shepard was a trailblazer for women in country music, who rose to fame in the 1950s with her honky-tonk style and frank lyrics. She was a member of the Grand Ole Opry for 60 years and a Country Music Hall of Fame inductee. But behind her success and popularity, she also faced personal tragedies and health challenges that eventually led to her death in 2016.

Jean Shepard was born Ollie Imogene Shepard on November 21, 1933, in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. She grew up in a poor sharecropper’s family that moved to California during the Great Depression. She developed a passion for country music at an early age, listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio and forming an all-female band called the Melody Ranch Girls. She was discovered by Hank Thompson, who helped her sign with Capitol Records in 1952.

Shepard’s breakthrough came in 1953, when she recorded a duet with Ferlin Husky called “A Dear John Letter”. The song was a half-spoken letter from a woman to her soldier husband, telling him that she had found another love. The song resonated with the audiences during the Korean War and became a huge hit, reaching number one on the country charts and number four on the pop charts. It was also the first post-World War II record by a female country artist to sell more than a million copies.

Shepard followed up with more hits, such as “A Satisfied Mind”, “Beautiful Lies”, and “Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar)”. She also joined the cast of the Ozark Jubilee television show and the Grand Ole Opry in 1955. She was one of the few female stars on the Opry at the time, along with Kitty Wells and Minnie Pearl.

In 1960, Shepard married fellow Opry star Hawkshaw Hawkins, who was known for his good looks and rich baritone voice. They had a son, Don Robin, in 1961, and were expecting another one in 1963. However, their happiness was cut short when Hawkins died in a plane crash on March 5, 1963, along with Patsy Cline, Cowboy Copas, and Randy Hughes. Shepard was eight months pregnant at the time and gave birth to Harold Franklin Hawkins II on April 1.

Shepard was devastated by the loss of her husband, but she returned to work soon after giving birth. She continued to record and perform, releasing more singles and albums throughout the 1960s and 1970s. She also remarried in 1968, to musician Benny Birchfield, with whom she had two more sons, Corey and Jesse.

In later years, Shepard developed Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disorder that affects the nervous system and causes tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with movement and balance. According to DrMirkin.com, Parkinson’s disease can also affect the heart and cause irregular heartbeats, low blood pressure, and heart failure.

Shepard struggled with her condition for several years, but she did not let it stop her from performing. She remained active on the Opry stage until 2015, when she announced her retirement after celebrating her 60th anniversary as a member. She was also honored by the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2011, becoming one of only three female solo artists to be inducted at that time.

Shepard died on September 25, 2016, at the age of 82. According to Wikipedia, she died of Parkinson’s disease at her home in Hendersonville, Tennessee. She was survived by her husband Benny Birchfield and her five children.

Jean Shepard was a pioneer for women in country music, who sang about love and life from a woman’s perspective. She influenced many other female artists who followed her footsteps, such as Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Tammy Wynette, Reba McEntire, and Miranda Lambert. She was also admired for her honesty and courage in facing her personal challenges and health issues.

Shepard once said: “I’ve always tried to be honest with my fans. I think they deserve that.” She also said: “I don’t want people feeling sorry for me because I have Parkinson’s disease. I’m not going to let it get me down.”

•

Remembering Jean Shepard

Use the form below to make your memorial contribution. PRO will send a handwritten card to the family with your tribute or message included. The information you provide enables us to apply your remembrance gift exactly as you wish.