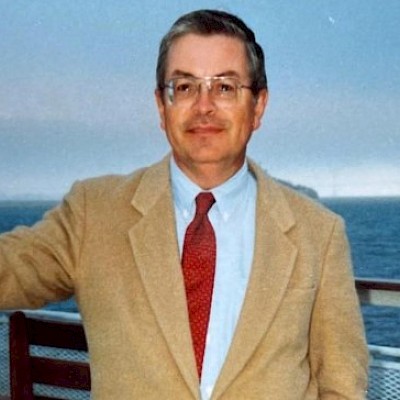

Charles E. Baublitz Jr., a decorated retired Anne Arundel County firefighter who was an enthusiastic rail fan and devoted collector of model trains, died of multiple medical conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, Sunday at his Woodbine home. He was 76.

“Charlie was a class act. He was more than a friend, he was a brother to us in the fire service,” said Bill Poteet, a retired Anne Arundel County firefighter, who is president of the Anne Arundel County Retired Firefighters Association. “He was well liked and well respected and was very conscientious about the job and took it very seriously.”

Charles Edward Baublitz Jr., son of Charles E. Baublitz Sr., a Bethlehem Steel Corp. worker, and his wife, Ethel May Thompson Baublitz, was born at home on Wasena Avenue in Brooklyn Park.

Mr. Baublitz, who was raised in Brooklyn Park, attended Brooklyn Park and Andover high schools, and later earned his GED diploma while serving in the Army from 1965. He spent a year in the Netherlands and Belgium serving with NATO Headquarters Allied Forces Central Europe.

Mr. Baublitz’s path to becoming a firefighter began at 16, when he became a volunteer at the Ferndale Volunteer Department.

“I first met him when I was 16 and we were both volunteers at Ferndale. Charlie was a little bit older, and I looked up to him,” Mr. Poteet said. “He taught me a lot about firefighting and was truly a role model for me.”

After he was discharged from the Army, he was working at General Motors Corp. on Broening Highway, and after taking the Anne Arundel County Fire Department test as a member of Class Three, he was hired as a firefighter in 1969.

“He was at General Motors and then they went on strike,” said his wife of nearly 51 years, the former Eleandra Ann “Ellie” Mullenax, a former longtime Baltimore Sun newsroom editorial assistant. “The fire department called him on Friday, and he started working there on Monday.”

Mr. Baublitz was assigned to Ferndale Station 34, where he spent 27 1/2 years and worked his way up to Firefighter III, or engineman, who is also known as a pump operator and equipment driver.

Ron Galella, the celebrity photographer whose pursuit of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis resulted in a restraining order against him after he stalked her for years, died at age 91 on April 30, 2022, at his home in Montville, N.J., of congestive heart failure. (Carlo Allegri/AP)

“I worked with Charlie at various times and he was a very good engineman and driver, and if you had to rely on a pump operator and driver, he was the guy you wanted to be with,” Mr. Poteet said.

The two men along with fellow firefighters were called to a Glen Burnie house fire one day where a mother and two children were inside the house.

“Our crew had been ventilating the fire and then we went inside looking for the victims who were rescued by another crew as we went in,” said Mr. Poteet, who attained the rank of captain and retired in 1995 from the Linthicum Station. “And we were given a commendation for our participation in the rescue operation.”

Ms. Baublitz said: “Charles earned several commendations for performance in helping save lives during serious house fires.”

Jim Lenz, a fellow firefighter, had worked with Mr. Baublitz at Ferndale in the mid-1970s, and retired from the department in 1996 as a pumpman.

“Charlie was a hands-on guy who could fix anything. There wasn’t a lot of money for the department in those days, so we had to fix things ourselves,” Mr. Lenz recalled. “If we got into trouble, Charlie got us out of it. You’d watch him and you learned by osmosis.”

He praised Mr. Baublitz for being a “master fabricator.”

“If he needed a part to fix the equipment, he made it himself so we could keep the fire engines moving,” Mr. Lenz said. “At the time, we were still driving 1957 engines. Charlie was an excellent driver. He never had any crashes and got us there on time, so we could put the wet stuff on the red stuff.”

During off-hours, Mr. Baublitz and another firefighter, the late Melvin Morrison, operated a home improvement business for 25 years.

“Whether they were fighting fires or installing siding and windows, they knew what they were doing,” Mr. Lenz said.

Lois H. Feinblatt was a pioneering sex therapist who practiced with the Johns Hopkins Sex and Gender Clinic for more than three decades and was a also a philanthropist. (handout)

“Charlie was quiet, unlike most fire department people who tend to be boisterous,” Mr. Lenz said with a laugh. “He also liked doing the occasional prank. He’d sneak up on you, so you really had to keep him in sight. No one ever got hurt and they were just fun, and he was just good at it.”

Robert Bailey, who worked with Mr. Baublitz for nearly eight years at Ferndale, retired in 1992 from Engine 32 in Linthicum where he had been a pump operator.

“Charlie was a born leader who liked to teach,” Mr. Bailey said. “We got along together and I used to eat breakfast, lunch and dinner at the firehouse with him during a shift. He was just a jolly old guy who’d help anybody and would give you the shirt off his back.”

He added with a laugh: “And I became his personal chef.”

Mr. Baublitz spent the last few years of his career at Glen Burnie Station 33, from which he retired in 1996. He later returned to work in 2005 when he took a job as a stockman for Boscov’s Department Store in Westminster Mall, until retiring a second time in 2017.

He had belonged to the fire department’s bowling league for several years and was an active member of the Anne Arundel County Retired Firefighters Association.

Mr. Baublitz’s fascination with railroading and model railroading began in his childhood, his wife said.

Through the years, he had amassed an enormous collection of trains of all gauges and an operating layout that eventually overwhelmed his basement and required the building of what was called his Train House in the yard of his Woodbine home.

“In 2014, we built a 24-by-30-foot building that Charles filled with his trains,” Ms. Baublitz said. The building also included a working layout, along with shelves and shelves of locomotives, and freight and passenger cars.

Mr. Baublitz also had a taste for the real thing — he visited his favorite operating railroad, the Cass Scenic Railroad, many times. The lumber railroad dates back to 1901.

The 11-mile-long standard gauge railroad, officially known as the Cass Scenic Railroad State Park in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, is entirely steam-operated, with the majority of its seven-engine fleet dating to the 1920s, and its most recent to 1945.

Other interests included reading science fiction and going to yard sales and flea markets. He was also a cat fancier.

In 2001, he realized a life dream when he and his wife traveled to England where they spent weeks visiting ancient sites such as Stonehenge.

Funeral services will be held at 1 p.m. Friday at the Burrier-Queen Funeral Home at 1212 W. Old Liberty Road in Sykesville.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Baublitz is survived by two sons, Charles E. Baublitz III of Woodbine and Jerid Baublitz of St. Petersburg, Florida; a brother, James Baublitz of Brooklyn Park; a sister, Ruth Hopson of Westminster; a half-sister, Betty Morgan of Hagerstown; four grandchildren; and several nieces and nephews. A daughter, Jennifer Baublitz, died in 2007.