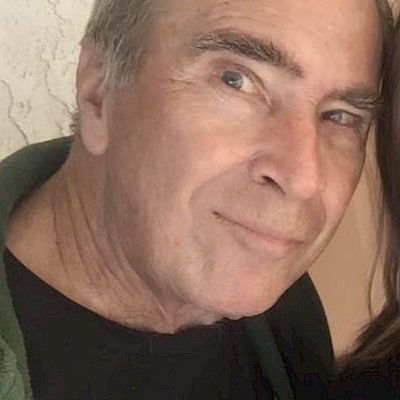

JonPaul Stonehuerner

He was born John Paul Stone, November 8, 1937, in Arkansas City, KS. He died in his sleep Dec. 31, 2022, which Kenny Rogers thinks is the best you can hope for. Not only did he get to die in his sleep, he got to die at home. Only about 20% of the people in this country die in the familiar surroundings of home. He could not have done it without the help of Rose Ogu and Frank Doonan. What a difference they made in his life and his death. The official cause of death was Parkinson's disease even though the Parkinson's Foundation states that no one dies of Parkinson's. The actual cause of death, which, strangely, cannot be put on death certificates in this country, was old age. He was the only one in his immediate family to reach the age of 85. He died because he had reached the end of his natural life span.

Somewhere over the first 30 years or so of his life he came to be Jonpaul Stone, commonly known as JP. On June 11, 1977, he married his beloved Jackie Huerner and became Jonpaul Stonehuerner. His mother, Ruth Bernard Stone, published a Pioneer Cookbook with recipes for all sorts of wildlife, had a quilt-making business, and was a dental assistant. His father, Walter Stone, was a dentist who got out of dental school in 1929. Unable to set up a dental practice, he joined the CCC, and the family moved to Washington and Oregon. He was drafted directly into the army at the start of WWII, and JP moved with his mother and his brothers to her grandparents' farm in Kansas where they lived without electricity or indoor plumbing. Some of his fondest early memories were of sitting on the sacks of grain while his grandpa drove to the mill in his horse-drawn wagon.

When the war ended, the family moved to Topeka, which he always considered his hometown. While still in high school, he joined his brother Bernard to study art with Emil Bisttram in Taos. After graduation from Topeka High he studied at the Art Students' League in New York City with George Grosz, Robert Brackman, and Frank Reilly.

At this point in an obituary it is traditional to say what the deceased did for a living so here goes. He always considered himself an artist and at times supported himself solely by selling his artwork. At other times, most of the time actually, he found it necessary to do other things, some of them tangentially related to the art world. He worked in frame shops and small galleries, sometimes as a wage slave and sometimes as an unofficial manager, and some of these galleries also sold his artwork. In silk-screening shops he just cleaned screens as teenager. Later he took his portfolio to a shop in Hog Eye, AR, and was hired as a T-shirt artist. He once had a job drawing in the colored lines that showed the routes of the little independent telephone companies in Kansas. He painted houses inside and out, but to say just that gives no idea of the wide-ranging discussions that took place when his fellow house painters were or had been theology students. He did layout for a yearbook company. He worked up gravestone rubbings, including those of Bonnie and Clyde who are buried in Kansas. He painted a few signs and also a couple of murals with his brother Bernard. In the 50's he and his brother Lee were paid beatniks in a upstairs coffee-shop, Big Daddy's, on Westport Road in Kansas City, Missouri. Big Daddy bought them black turtlenecks, and Lee played the guitar and sang songs about the customers while JP did sketches of them. He was also a sketch artist/ bartender/bouncer in a bar on skid row in Seattle.

Then there were a lot of jobs that were in no way connected with painting or art. He worked in restaurants as a cook, a waiter, a dishwasher, and a cashier, and he was the counterman in a Jewish deli. He was a paid extra in movies and TV shows. Like everyone with a resume like this, he drove a cab, first in San Francisco and later in Kansas City. Long before the days of the GPS he learned not just the streets in San Francisco but how to get from one place to another by going around the hills rather than over them. That knowledge also served him well in what turned out to be one of his favorite jobs, with the Pacific Lighting and Electric Company where he did whatever needed to be done: assembly, shipping and receiving, delivery.

He and a colorful crew did foundations, framing and finishing on a couple of owner-built houses in Northwest Arkansas. He worked in machine shops in Kansas City and Oklahoma City and cabinet shops in Durham and Hillsborough, NC, as well as being a flunky on the production line for White Furniture.

In Eureka Springs, AR, he pretty much did it all for a small company that made furniture from weathered oak. They bought the oak from local farmers and sold the furniture in a shop in Eureka. JP first had to convince the farmers, who clearly thought he was crazy, that he really was going to replace the beat-up old boards with new ones-and pay for the wood as well. He was as good as his word and got a few takers. Back in the woodshop he built the shelves, tables, and other things, and then waited on customers in the store.

He did what people who have never done it know as casual labor. He unloaded boxcars of fiberglass insulation on hot summer days. He detailed cars and occasionally drove them to another location while working for a Mercedes dealer. As with many other jobs, his duties were quite different from the way they were explained when he was hired. He picked peas in Washington State and came to count his blessings when he picked Brussels sprouts and artichokes in the fields of Northern Cal alongside mostly Filipino co-workers, many of whom had not seen their families for decades. He tried his hand at being a travelling salesman, selling enzyme-based drain cleaners years before they were available in stores or online. His work for a high-tech company in the Triangle consisted mostly of moving walls to accommodate their ever-changing corporate structure. "It's a house of cards," he muttered half to himself and heard the phrase whispered for days as he moved among the flimsy cubicles. He was a groundskeeper for a while at the University of Arkansas, a job he considered somewhat demeaning even though he looked charming and bucolic with a pipe in his mouth and a rake in his hand. The Chamber of Commerce of Eureka Springs paid him, but probably never very much, to answer tourists' questions. He assembled and painted dinghies and generally made them seaworthy while working for a small company in Davenport, CA. He took the census. He rued the day he hired on with a company that installed greenhouses where he had to climb across narrow strips of metal to secure big pieces of glass in place. He worked on the line at the Campbell's Chicken Soup plant in Fayetteville, AR, and never again willingly ate poultry.

While living in Kansas City he answered an ad in the Kansas City Star for a job based in Dallas. He drove there and was hired to deliver a wildlife film to movie theatres in small towns, mostly in the South and Southwest. During this gig, he caught pneumonia and almost died in Truth or Consequences, NM. He lost consciousness and came to surrounded by smiling women in white whom he first thought were angels but were really nurses. He was run out of town at gunpoint by a jealous husband in Spring Hill, LA, (He didn't know she was married), and he discovered Eureka Springs, Arkansas, which was to be his home for the next several years. Probably his most colorful job was as a roughneck in the oilfields of Kansas. This kind of work was easy to find. Any able-bodied man could drive out onto the plains at night where drilling rigs were the only thing lit up and get hired on the spot.

It's impossible anymore to know the sequence of these endeavors except the first and the last. His first job unloading trucks and stocking shelves at the Piggly Wiggly turned into a warning about the ways of the world. After they'd unloaded a truck full of watermelons, the truck driver offered JP a dollar to come with him for another hour, an offer so extravagant he couldn't refuse. They drove out into the country, out of sight of any houses, and JP helped the driver drag big heavy rocks out of the truck and throw them by the side of the road. Being only 14, it took him a long time to figure out why the rocks were there. His 'career' ended when his knees gave out while he worked on the line at White Furniture Company under conditions that might have appalled Charles Dickens. These are just the jobs he managed to get paid for. Among his unpaid positions-spiritual advisor to the Broken Dreams Trailer Park.

Strange to spend so much time describing his employment when it was never the focus of his life. Life itself was. In addition to creating his own art, he deeply appreciated the work of others. The first time he saw Frederick Church's 'View of Jerusalem' at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, he spent the rest of the day taking it in from every possible distance, every direction, every possible angle of lighting.

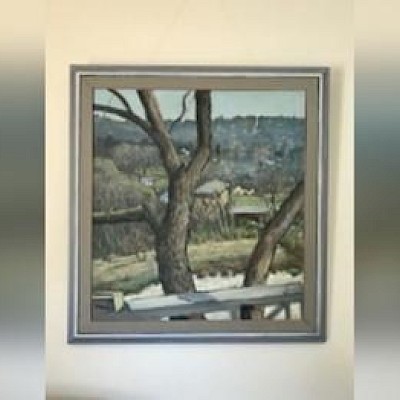

Although he continued to paint well into his 70's, he never repeated the bursts of artistic activity he experienced in San Francisco and Eureka Springs and environs (I would include here 'The View from Fort Leverett' shown above painted in his studio on N. Leverett Ave., Fayetteville AR).

He gained some local fame for his associations with pop-culture figures from the 60's. His magician friend Gerard Kolbetter lived down the hall from Janis Joplin. His musician friend Tom Hobson was friends with Jorma Kaukonen of the Jefferson Airplane, and you never knew who would stop in to jam. He knew Jerry Garcia slightly from just being around the Avalon and the Fillmore. He rented studio and living space in a huge Quonset hut in Sausalito. Buffalo Springfield used another part of the building for practice sessions. He thought they sounded awful. Maybe bad acoustics.

But he always found the writers more interesting than the musicians. He knew Richard Brautigan from the Coffee Gallery on San Francisco's North Beach. The only job he said he would have willingly done without pay was at the Pomegranate Gallery across the alley from Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights bookstore. He sold his and others' paintings at the gallery. He met Gary Snyder when he was hitchhiking down Highway One, and Snyder stopped to give him a ride. They kept in touch for several years through Ferlinghetti and City Lights. He never met Kerouac, but also through City Lights he had the misfortune to encounter Neal Cassidy, a royal pain the ass if there ever was one.

He looked upon the 60's in San Francisco as a kind of folk festival where the peasants celebrated the harvest. That experience can never be repeated because, unlike now, living was so easy. He could work as an extra for a couple of days and pay his part of the rent for rooms in a big old Victorian house. One day he walked out of the house he was sharing with Tom Brand to see Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters bus parked in front. Their spirit was in the air even though he never knew Kesey.

Of course, the San Francisco area was also a hotbed of political activity at the time with anti-war demonstrations throughout, the Black Panthers based in Oakland, and the Free Speech movement centered in Berkeley. He went to a couple of Free Speech demonstrations in Berkeley and was haunted forever by the sound of billy clubs cracking heads. One day he was strolling down Telegraph Avenue toward the university minding his own business when he was confronted or very nearly confronted by a phalanx of heavily armed police heading toward him, completely blocking his way. When he saw them and realized they saw him, he opened the nearest door, ran up a flight of stairs, and entered an apartment where he was welcomed warmly with smoke and wine.

At some point California just got too crazy. Stuff like that simply didn't happen in the Midwest. He moved back to Topeka and then to Kansas City, MO, where he met Jackie. They were married there in All Souls Unitarian Universalist Church. Then, as noted above, he discovered Eureka Springs, which is more visually stimulating than KC for sure. Jackie followed him to Arkansas where she found interesting but not particularly lucrative work at the university in Fayetteville. After scraping out a living for seven years, they moved to Durham. Asked later why he came to North Carolina, he said, "to join the middle class." In this he was not entirely successful since jobs paid better in North Carolina, but it cost more to live here. Growing up a Kansas Freestater he had feared even to enter the South but came to feel at home in the gentle warm climate of North Carolina.

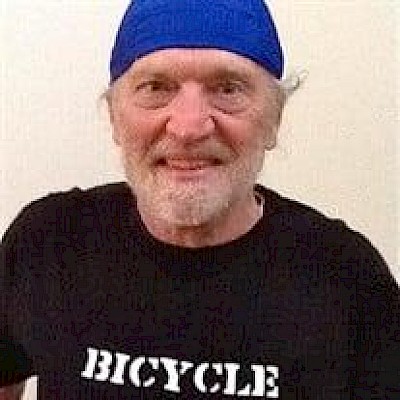

Had he not moved to the Old North State, he never would have found Cup-A-Joe's and the myriad of amazing people he met there-intelligent, well read, clever in conversation but also compassionate. Sadly, he developed dementia near the end of his life that, among other things, rendered his speech generally unintelligible. Long after they had figured out conversations with JP were going nowhere, they always seemed genuinely happy to see him and made room for him at the table. You know who you are. Not knowing any one of you would have left an emptiness. Not knowing any of you is unimaginable.

His 85th birthday, November 8, was the day of the 2022 mid-term elections. Rest assured that even in his most demented state, he never voted for a Republican. As for his last words, it's a little hard to say for sure. He continued to mumble incoherently. During the last few days he would call out, "Jackie," but no one could figure out what he wanted to say to her. Probably just for her to be there, which she was. The last words he spoke clearly that indicated he was aware of his situation were his response when Jackie stupidly tried to assure him that he was okay, that everything was all right, "Bull shit."

He is survived by his wife of 45 years and soul-mate forever, Jackie Stonehuerner of Hillsborough, his sister-in-law Sylvia Stevens (widow of Bernard Stone) of Leavenworth, KS, brothers-in-law Richard Huerner (wife May) of Lake Orion, MI, and Jim Weaver (widower of Diana Stone) of Topeka, KS, numerous nieces, nephews, great nieces and nephews, and great, great nieces and nephews. How he loved his big, diverse, talented, never boring extended family! Probably the ones who had the greatest impact on his life were his nieces Chelsea Appenfeller of Topeka and Becky Richmond of Prairie Village, KS, and especially his nephew the late Greg Stone of Ottawa, KS. He and Greg lived together in two or three places in the Westport area of Kansas City when JP was young, and Greg was really, really young. They seemed to form bonds that were never broken even though their lives took very different courses. His brother Bernard Stone of Leavenworth, KS, and sister Diana Stone of Topeka preceded him in death. His niece Becky said that to them he was "not only a brother but a friend, a confidant, and a fellow fun-seeker." Especially since he had no children, and his siblings preceded him in death, it seems appropriate to include in this section friends that stood by him for fifty years or more: Dan Pinckley of somewhere outside West Fork, AR, Tom Brand of Silver City, NM, the late Jimmy Gates of Cedar Point, KS, and James Yale of Rogers, AR.

'Whatever' being a good Kansas word popularized by Bob Dole among others, a Whatever gathering will be held in JP's honor at the Exchange Club Building on Exchange Park Lane Feb. 19, 1-4 pm, followed by a free pitcher of beer at Nash Street Tavern starting at 7 p.m. to the first ten people who mention JP's name whether or not they can say Stonehuerner. There will also be a graveside service in Mt. Vernon Cemetery, Winfield, KS, when his cremains will be interred next to his mother's grave April 8. As Mike Stradtner observed, "The end of an era."

•

Remembering JonPaul Stonehuerner

Use the form below to make your memorial contribution. PRO will send a handwritten card to the family with your tribute or message included. The information you provide enables us to apply your remembrance gift exactly as you wish.